I’m not an expert in global trade, but it is worth thinking a bit about the basic economics these days. For decades, the United States has led the world in a movement toward fewer trade restrictions, but it certainly appears that protectionism and trade restraints are now the political fashion here. What will be the result?

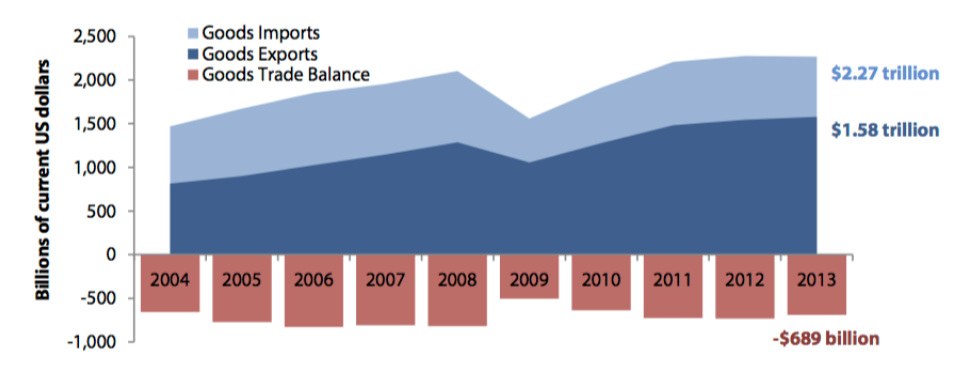

We all know by now that the US runs a goods trade deficit; the figure below from the 2013 US Trade Overview (from the International Trade Administration of DOC) shows a roughly $700 billion goods trade deficit:

The US runs a services trade surplus, which reduces the total trade deficit somewhere closer to $450-500 billion.

If global trade were a zero-sum game, then a trade deficit would mean that the US is getting poorer each year, and net exporters would be getting richer. But global trade is not a zero-sum game, because economics is not a zero-sum game. The entire point of trade, whether global or local, is to create more value via a trade transaction than would exist without the transaction; clearly, this is not zero-sum!

A trade deficit, therefore, is just another statistic. It does not tell us much about winners or losers in the global economy. Policies that seek only to reduce trade deficits are, therefore, pointless. Restrictions on trade serve to potentially reduce or eliminate the value-creating activity that was the reason for the trading in the first place. We should be careful to create such restrictions.

Consider a simple example. Suppose the world contained people who live either location A or location B. People in location A create a single product AP that brings them all the sustenance, joy and happiness they could ever want. But to create AP, they must first create or acquire product BP.

The net wealth of people in A is simply v(AP) – v(BP), where the subtraction represents the cost of producing or acquiring BP. Suppose that if BP is produced locally in A, its cost is 3, but if produced in B, its cost is 1. Let v(AP) be 4.

The net wealth of people in B is most simply measured by some baseline plus v(BP). For each unit of BP they produce and sell to someone in A, they get net added value of 1. But, a person in A receives net value of 2 every time she buys a unit of BP from B, rather than produce it herself! In this system, each time a unit of AP is produced using a purchase of BP from B, a person in A gains 3 units of value, and a person in B gains 1 unit of value. Thus, in this example, the wealth of A rises faster than B. But A runs a continuous trade deficit with location B.

The economic value generated by each transaction in this simple example is +2; that is, 2 units of value are gained by trade. Each trade is not zero-sum. Location A, with its trade deficit, is earning a larger share of the benefits. But, indeed, the net wealth of everyone is increasing. Of course, you c ould also create an example where the location with the trade deficit is increasing its wealth at a slower rate than its partner. The point is that the existence of the deficit itself is not predictive.

Trade restrictions can certainly help prevent trading partners from increasing wealth, if that were the primary objective. It remains to be seen whether the US decides to relinquish its position as a leading proponent of free trade, and whether or not another nation assumes that leadership position.